Safely Evaluating Arbitrary User Code in Javascript

For my website ai-arena, I needed to run arbitrary code from users on both the front-end and the back-end. The game is a strategy game where ships compete to gather resources and destroy each other’s base. Users write the code that controls the AI of their team.

Constraints

- Users cannot modify the game except through API exposed to them

- Users may not access the DOM, Ajax, or any globals from either the browser or node environment (no access to Process, etc)

- User code needs to run in realtime. This means no use of an in-javascript interpreter

- User code needs to execute within a single game loop running at 60fps minimum. (no worker threads, too slow.)

- User code needs to safely exit if it takes too long to run or takes up too much memory.

- User code needs to have all exceptions handled to prevent crashing the server.

Front-end sandboxing

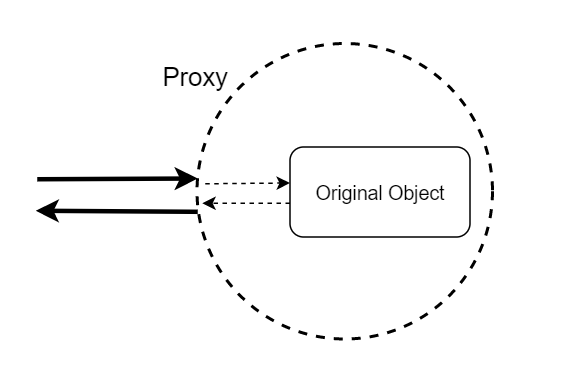

On the front-end it’s a fairly easy deal. I dont care if the user blows up their own browser. But I don’t want the user to be able to manipulate the game or access any globally available information. The best source I could find for sandboxing in the browser was here. I don’t fully understand the Javascript-fu being done here, but I understand that by proxying the “has” function of the “with” object prototype, you can hide global scope from the inner function (hooray, metaprogramming!). For those unfamiliar with proxies, they basically allow you to wrap an object and redefine its prototype methods. A good introduction can be found here.

Now that global scope is hidden, everything we want the user to have access to must be passed in explicitly. There is still one caveat though– if we pass in gamestate, then the user can modify the state of the game directly. Proxies come in extremely handy here for creating a “read-only” mode.

To prevent the user from setting their ship’s health to infinity, we can wrap the ship object in a proxy that has a trap for “set”. If the field is something we don’t want the user to modify, like health, we can “blacklist” it. If the field appears in the blacklist then we return null, and prototype.set(“health”) wont do anything.

If an object has nested objects, like a position or velocity vector, then we set a trap for “get”. When get is called for a field in this “graylist”, we instead return a deep copy of the object.

Here is the proxy for gameObjects that dont belong to the player (anything that isn’t their ships or home base)

const createGameObjectProxy = (gameObject : GameObject) => {

const grayList = ["transform","collider","resources"]

const blackList = ["spawnShip", "upgradeInteractRadius", "upgradeHealRate",

"upgradeMaxEnergy", "update", "start", "serialize", "queueShip", "trySpawnShip", "takeResources",

"healShip", "destroy", "render", "collide", "simulate", "shipQueue", "moveTo",

"seekTarget", "upgradeDamage", "shoot", "applyThrust", "breakup", "totalMass",

"getResources", "toString", "colors"]

const gameObjectHandler : ProxyHandler<GameObject> = {

get : (target : GameObject, prop : string) => {

const field = Reflect.get(target,prop)

if (grayList.includes(prop)){

return Serializer.deserialize(field.serialize())

}

else if (!blackList.includes(prop))

{

return field

}

return null

},

set : (target, prop : string, value, receiver) => {

return false

},

deleteProperty : (target, prop : string) => {

return false

},

defineProperty : (target,prop : string, attributes) => {

return false

}

}

return new Proxy(gameObject,gameObjectHandler)

}

I used a “blacklist” (I prefer the terms allowlist and denylist but using colors makes the graylist concept easier to understand in my opinion) and “graylist” so that anything not explicitly outlined (i.e. user-created fields), would be fair game to read. Imagine writing your AI to check the memory of all enemy ships and see if any of their fields matched the ID of a resource-rich asteroid. You could infer that their ship was heading to the asteroid, and you could fire a missile to destroy it and waste their time. Or you could figure out which of your ships was being targeted by an enemy ship, and return fire.

The proxy class

Back-end sandboxing

The back-end is a little more constrained. Users shouldn’t be able to crash the game with an infinite loop or blow up the memory of the host machine. Unfortunately there’s no way to know if a user’s code will run longer than allowed without running it (halting problem). One solution would be to run user code in a separate thread and have an async timeout run simultaneously. If the timeout completes before the thread, then the user code is too slow. Unfortunately threads in Node.js have a minimum overhead of about ~50ms. This is way too long, especially when I’m trying to run a game at 2ms-5ms/tick. User code needs to run in less than 500us.

The other option is to insert breakpoints into user code. This incurs some overhead, since perform a subtract and compare on every iteration of every loop. To parse user code into an AST tree, I used Esprima. In order to prevent users from overriding the value in the timer, the variable name of the timer is randomly generated each time the code is sanitized. Here we parse the AST tree and use the line number offsets to insert the breakpoints

Preventing memory bombs is very straightforward, the object is stringified and encoded as text. Each char is a byte. I allow users to allocate 8kb of memory, more than enough.

const size = new TextEncoder().encode(JSON.stringify(obj)).length

const kiloBytes = size / 1024;

Lastly, to prevent users from submitting shoddy code and losing matches via timeout, we only want to submit user code that has been proven to be performant. For this I just made a Lambda function that runs 30 timesteps of the game and will exit if the user code ever times out. Unfortunately the Lambda instances have varying performance, so the timeout threshold is significantly higher in the Lambda than in the tournament server. This could lead to users being greenlit by the lambda, but losing by timeout in actual online matches.

Since I am a js and software noob in general, I fully expect there to be holes in my implementation. If you have any suggestions, please reach out at my email!